Interviews on a New Spatial Paradigm in the Digital Age

Media theorist Lev Manovich has written, “The computer era introduces a different paradigm. This paradigm is concerned not with time but with space.”1 Indeed, departing from prior emphases on medium specificity and flatness, artists and theorists have developed novel approaches to thinking about space in visual imagery. Through the remediation of established media, software offers artists previously unthought-of ways to configure space. These spatial reconfigurations correspond to a recent reconsideration of the relationship between the human and technology. While the digital regime provides new democratic means of producing and distributing artworks, concomitantly, it establishes forms of control administered through a global network and through the free flow of international capital. Whether for good or for bad, the digital has proliferated and permeated all of social space, leaving us in a situation where there appears to be no inside or outside.2 In the following series of interviews, I asked several artists about the role of digitalization in spatially composing an image. All of the interviewees are preeminent American contemporary artists who have shown extensively around the world. While these are not the only innovators who are transforming visual representation, I chose these particular artists for several reasons. First, although they have all received international recognition in the contemporary art world, they are lesser known by European art historians and academics. Secondly, they each work in different media and employ disparate techniques. Finally, they each approach spatial composition and the digital from their own unique angle.

MICHELE ABELES

Michele Abeles (b. 1977) lives and works in New York City. She graduated from Yale University with an MFA, after receiving a Bachelor of Arts degree (BA) from Washington University, St. Louis. Abeles has had recent solo exhibitions and presentations at the Karpidas Collection, Dallas; Sadie Coles HQ, London; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; and 47 Canal, New York. Abeles’s work has been featured in group exhibitions at institutions such as the Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig, Vienna; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York; the Fridericianum, Kassel; and MoMA PS1, New York. Her works are held in various collections including those of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Aïshti Foundation, Jal el Dib, Lebanon; the Dallas Museum of Art; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; MoMA, New York; the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Some of your images look like stock photos and others you photographed yourself in ‘real’ physical space. In many of your works, you reference screen space, how we look at images on our computers and on our phones (fig. 1). You even evoke the swipe mechanism on an iPad or iPhone. Could you discuss the relationship between physical space and virtual space in your work?

For Re:Re:Re:Re:Re, my first show at 47 Canal gallery in 2011, I presented still life photographs with nude male models, bottles, and other objects. I staged them in my studio, but I wanted to use the camera and certain lenses to compress space in the same way that space appears compressed when you look at images on your laptop or your phone. I was thinking about the space inside the image, about the physicality of a body and what it becomes in digital space when you view it on-screen.

In my second show, English for Secretaries at 47 Canal in 2013, I became more interested in the person looking at images from the ‘outside.’ I considered the photographs as screens, and I wanted to explore the relationship between these screens and the viewer’s body, how we touch them and swipe them.

In my recent show, October, at 47 Canal,3 there were fewer visitors than usual because of COVID, but ironically [laughs], I focused more than ever on the viewer’s body in the physical space of the gallery. For this exhibit, I sized the photographs for the room; I wanted them to overwhelm the viewer physically.

Similar to Robert Rauschenberg, many of your digitally manipulated images combine diverse media such as painting, sculpture, text, and photography, creating complex spatial montages. Leo Steinberg wrote that in Rauschenberg’s work, the picture plane shifted from vertical to horizontal. This tilt effected a radical reorientation of art from an upright, two-dimensional window onto nature to a tabletop-like surface with three-dimensional objects on it, a “flatbed picture plane” similar to the flatbed printing press.4 Unlike Rauschenberg, you work with the zero-dimensional space of the digital. Things are not tethered to material reality; they don’t follow the physical laws of the universe. They depict pure space with no sense of place. Am I right to understand this as an exploration of the potentiality of digital composition, of spatial configurations that can be arranged in infinitely different ways?

Yes, as you said, Rauschenberg’s work played on this change in the viewer’s perspective. He combined the space of painting with the space of sculpture, so the body doesn’t move around the work in the same way as it would if the two media were separate.

I too am interested in the relation between the physical orientation of the image and the viewer’s perspective, how we have become used to looking at stuff digitally. So, many of my photographs are about the process of trying to understand what’s going on in the moment and the physical experience of interacting with this new digital space.

As for digital composition, I studied in a traditional photography program where you would take pictures of something, say a tree, and then choose the best one. This felt limiting, like there is only one version of each image. I began remixing some elements of my compositions to escape the stability and the preciousness of the image. I also started recombining aspects of my previous photographs to treat them like physical material that I could reuse in new works. Reconfiguring these things opens them back up but also closes them down. In other words, I don’t use repetition to create more content; I use it to take it away.

Also, in the early still life photographs we discussed, I took all of these generic items that don’t really go together and put them in the same image. I consider the space where they meet as a kind of non-space, or a transitional space, where you can’t pin anything down.

Speaking of non-space or transitional space, you seem to call attention to the space in between things. For example, you picture the space between images mid-swipe and between layers of windows open on a computer screen. In your compositions, the various elements appear scattered and isolated from each other. In other words, you do not present a parametric space of flows but rather a discontinuous, fragmented space.5 Could you tell me more about your interest in interstices? These spaces remind me of the synapses in biological brain circuits and in artificial neural networks. The brain is often compared to the screen, and recent film theory has argued that digital cinema pictures the working of a schizophrenic brain. Am I right to think of your photographs as “neuro-images”?6In graduate school, I became interested in how we use vernacular photography, pictures of family and friends, to create the narratives of our lives. We piece together these stories, particularly when we’re older, as an attempt at remembering. We have to fill the spaces in between to try to figure out what happened, which is inevitably an impossible task.

Then, as I mentioned, I started reusing elements, mixing everyday items, and playing with layers and lenses in my images. In some of my photos, the layers of windows relate to Joan Jonas’s work, which has greatly inspired me. In her performances, Jonas often uses image layering, but she does it in physical space. I am interested in how we view layers of images on-screen and the interstices where everything starts to mix together.

I’ve also thought a lot about the effect of the internet on our brains and our attention spans. I don’t know enough to speak about schizophrenia in a clinical sense, but I know how it can be used as an adjective to describe digital culture, and my work does relate to how we consume and see images as a form of ‘schizophrenia.’

As mentioned, in your still life compositions, you juxtapose generic items such as wine bottles, newspapers, cigarettes, cheap fabric, terracotta pots, fragmented anonymous body parts, and stock photographs of nature. They form a kind of “junkspace”7 where everything, whether it’s a human limb, a consumer object, or a tropical plant, has the same significance as any other. They remind me of the bargain bins at discount stores. Like the non-biodegradable trash floating in the ocean, these images never go away. Or, to come back to the “neuro-image,” they are like these useless thoughts that always seem to return to haunt our minds. Certain theorists have associated the photographic image with death, but silicon-based life never really dies. For this reason, I associate your pictures with the undead. This relates to your current exhibition, October, where you present a series of photographs of the Halloween decorations displayed in people’s yards. Am I right to think of your work in terms of zombies?8

I hadn’t thought about that, but yes, we could consider the recycled elements in my pictures as these zombie-like anonymous bodies. It’s true that, today, images never entirely disappear, and they proliferate, just as in horror movies when the undead keep coming in waves. They are like these endlessly reproducing copies of ‘real’ humans. This relates to the question of reality and what we believe to be true or not. With my show October, I was partly thinking about that in terms of politics. Especially since we’ve had this president [Donald J. Trump], there’s this idea of ‘fake news’; we no longer know who is telling the truth. There is no baseline anymore, so we are all living in these different realities; we have different psychic spaces. I thought it would be funny to present these pictures of, say a plastic skeleton, and pass them off as documentary images, as facts, when they are photographs of these imaginary scenes but taken in physical space. These exaggerated arrangements of ghouls, witches, and dismembered bodies reflect the arranger’s psyche, but then the viewer also has to fill in the gaps. Here, again, you have this convergence of different spaces that become an ungrounded non-space.

MARK BARROW AND SARAH PARKE

Husband-and-wife team Mark Barrow (b. 1982) and Sarah Parke (b.1981) live and work in New York City. Barrow received his MFA from Yale University. Barrow and Parke each received a BA from the Rhode Island School of Design. Their work has recently been exhibited at JDJ | The Ice House, Garrison, NY; La Capella Cavassa, Saluzzo, Italy; the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University, Waltham, MA; White Columns, New York; Le 109, Nice; ZERO..., Milan; Galerie Almine Rech, Paris and Brussels; Elizabeth Dee, New York; Power Station of Art, Shanghai; and the Musée d’art Moderne de la Ville de Paris.

The loom is considered a precursor to the computer, and your work has explored the relationship between weaving, visual systems, and the digital. The digital, which literally means the digits of the hand, can imply touch while also describing incorporeal information. In your work, you play on this dichotomy between the tactility of weaving and the opticality of painting. Could you explain some ways that you've used digital tools and referenced computing in your work? How has the digital influenced your spatial compositions?

MB: It's interesting to think of the digital in relation to its literal meaning. We start most of our compositions by drawing them with our fingers on an iPad or phone. We use a fairly rudimentary app that translates our fingers’ movements into bulbous lines, like finger painting as a child or writing your name in the sand. For us, there is a direct correlation between this digital act and the first cave paintings. Those first paintings were everything – abstraction, representation, innovation, giving an idea a form. In a way, all art thereafter has been an attempt to recreate those first moments. A finger on an iPad is a recent iteration that circles back to the original act in a lovely way. After all those tens of thousands of years and technological advancements, we’re still just drawing with our fingers.

SP: Yes, we then translate our computer-drawn composition from pixels-on-screen to paint-on-fabric. The bulbous lines become containers that hold different information. We often trace the threads of the fabric with paint using a small brush the size of one weaving pick (a single weft thread). A pick goes either over or under the warp threads. This binary predates the computer. We further play with this idea by also painting the weaving draft (a pixelated notation of the picks) and painting the tie-up (a numerical notation of which threads are raised to create the fabric). The latter looks like the binary digital code of zeros and ones.

You have used synaesthesia as a metaphor for your work. Synaesthesia is a neurological condition in which an individual conflates multiple sensory experiences from the same stimulus. For example, a synesthete can perceive numbers as colors or vision as touch.9 With the digital, similar to synesthesia, every medium can be transformed into another. Could you discuss this relationship and your interest in synaesthesia?

MB: We can only understand concepts through other concepts. Art allows us to see something in a new way, to see a concept through a new concept. That is what makes art interesting. Synaesthesia or the digital seem like apt metaphors or even tools to help facilitate this mode of working.

You have stated that your work reduces materials to their “most basic forms until everything becomes interchangeable.”10 Reductionism was central to modernist abstraction as well as to the dominant scientific paradigm of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But it seems to me that your work is as much about complexity as it is about reductionism, and an interest in complex systems is central to networked society and contemporary science.11 Today, scientists use computers to visualize the emergence of complex forms that are impossible to observe in physical space. In the same vein, you have likened your practice to scientists’ quest to understand the world beyond the Standard Model of particle physics and have stated that “things in the field of physics like commingled particles, non-locality, and inflationary theory may point to new understandings of space.”12 Could you elaborate on the link between your work, complexity, and alternative scientific models of space in the digital age?

MB: This question brings us back to the idea that people can only understand concepts through other concepts, a conceit advanced by the linguists George Lakoff and Mark Johnson.13 They write about subjectivity and its relationship to phenomenological physical experience. They argue that our subjectivity binds us, and the details of our corporeal existence limit our concepts. For example, the fact that our eyes and feet face the same direction, and we are biologically disposed to a front/back orientation determines our conception of space and time (moving forward, passing, standing still). Sometimes in art, it feels like everything has been done before. How can anyone make anything new or interesting? But when we read about contemporary science and see that, despite our corporeal limitations, scientists are still coming up with new (even radical) ways to view the world, it is really inspiring.

SP: Maybe other artists don’t have to do this in their practices, but we need to reduce things to understand them, and we must do this first in order to make anything more complex. We learned this in our undergraduate education, which was modeled on the Bauhaus and required a “foundation year” (learning the basics of drawing, two-dimensional design, and three-dimensional design) before moving on to a field of study. We have spent years making work based on the idea that a weaving pick = a pixel = a brushstroke. It feels like only recently, we have developed a language that we can use to make more complex compositions.

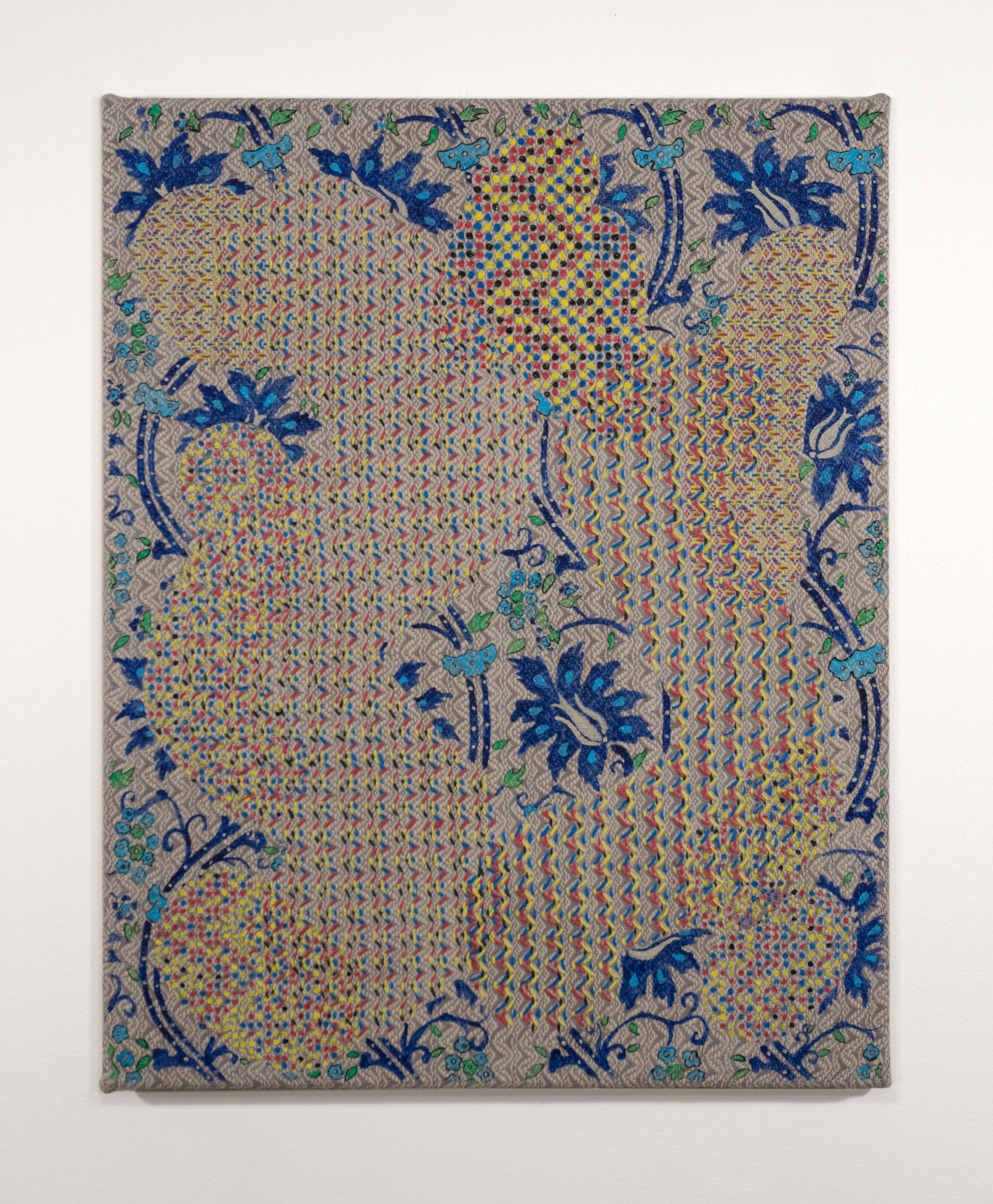

Your work Origin (2019) (fig. 2) has a floral pattern based on an Islamic tile design. In your recent exhibition Future Homemakers of America,14 you presented this work beneath a window with an aperiodic tile motif. As the press release states, “Taken together, one can draw a link between their underlying geometries, suggesting infinite expansion and a sense of spirituality.” Your continuously looping animation of an exploding star also seems to concern infinity and the digital. This statement brings to mind Laura U. Marks’s book Enfoldment and Infinity, which situates the origins of digital culture, particularly the algorithm, in ancient Islamic art. Tracing the connections between Islamic aesthetics and new media art, she describes an algorithmic aesthetic experience where the image functions as an interface to information and information is an interface to infinity. Could you expound on this relationship between infinity, information, and image?

MB: I don’t think the digital embodies any new concept, but because it accelerates everything and pervades our culture, it foregrounds already-existing concepts, structures, and ideas that were perhaps not as prevalent before, at least not in wider, popular culture. The argument that digital culture has its origins in ancient Islamic art is similar to the idea that the computer has its origins in the loom.

SP: We haven’t read Laura U. Marks’s book, so we probably shouldn't speak to her algorithmic aesthetic experience. But we are really interested in patterns, both as decorative motifs and as images, that through repetition do not necessarily represent what they depict but rather become interchangeable pieces of information. As you mentioned before, our work has always sought to reduce forms to their most basic components. The way we work with images is no different. If everything is interchangeable, you can better make connections across seemingly disparate concepts.

ALEXANDER CARVER

Alexander Carver (b. 1984) lives and works in New York City. Carver is a graduate of Cooper Union, New York, and received his MFA from Columbia University, New York. Carver’s work has been exhibited and screened in international venues and in festivals including Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York; Tate Modern, London; Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin; Lincoln Center, New York; Berlinale, Berlin; Biennale of the Moving Image, Geneva; the Melbourne International Film Festival, Melbourne; the Brooklyn Academy of Music, New York; the Locarno International Film Festival, Locarno; and the Vancouver International Film Festival, Vancouver. Carver’s works are held in the collections of the Ringier Collection, Zurich; the Langen Foundation, Neuss; and the GOME Art Foundation, Hong Kong.

What digital tools have you used in your paintings? In these works, you have made specific references to the software program AutoCAD. Have you used this and other digital programs? And if so, what spatial effects have resulted that would not have been possible through traditional means?

In the past, I have worked for architects and as a contractor. I think this is the principal reason for my interest in the built environment and the attendant computer-based design aids used by architects. Because paintings hang on the interior building envelope, they are always framed by and contextualized within architectural space. Historically, there are many interesting ways in which paintings, either as discrete objects or murals, refer to their built-environment context. Altarpieces, for instance, would sometimes invoke a trompe l'oeil effect that not only mirrored some of the architectural elements surrounding it but also imitated the lighting conditions and shadows that illuminated the cathedral itself. This would produce the effect of a ‘virtual’ extension of the ‘actual’ space. In this regard, painting prefigured virtual reality.

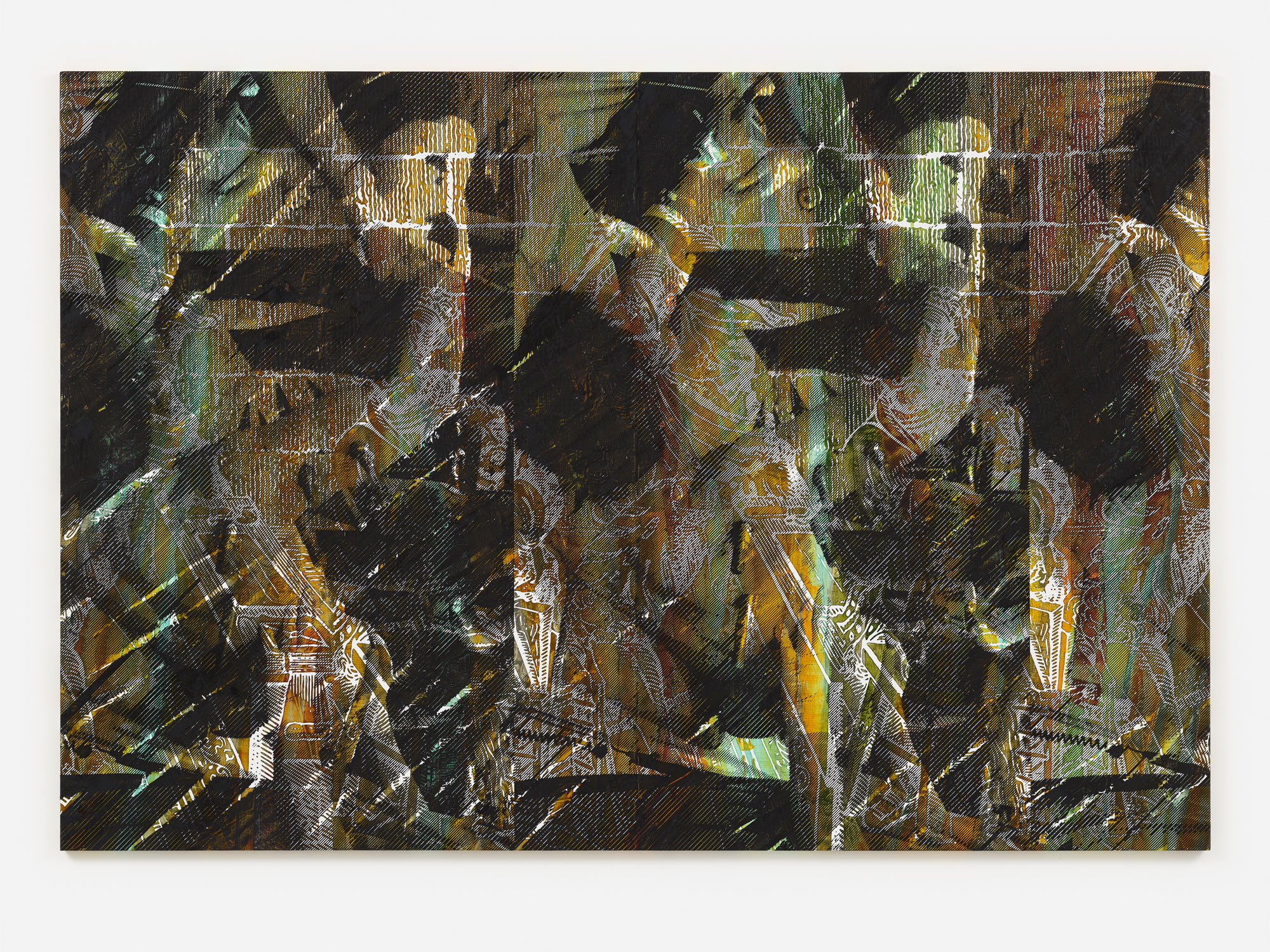

In my current painting practice (fig. 3), I often think through diagrammatic and spatial concepts using Sketchup, Photoshop, and Illustrator. I am partly interested in these programs for the interface logic that they impose upon one’s thinking. The layering and compression of digital tools make possible certain kinds of compositional density and visual disorientation. I then interpolate this computer-based exploration into an analog process achieved with paint. One of my favorite ways to do this is by cutting elaborate stencils out of vinyl from vector files I generate myself using Photoshop and Illustrator. In addition to interpolating digital space into painted space, I also enjoy exploring analog painting processes that invoke or imitate digital effects. I often achieve this with frottage: I place objects behind the canvas and make an impression of them with oil paint. This creates an uncanny effect that appears hyper-dimensional and highly rendered but is also entirely flat and devoid of any conventional strategies used in painting to achieve ‘realism.’ This indexical mark-making leaves a painterly ghost of an actual object on the membrane of the canvas. This process is analogous to the indexical data-points in 3D scanning technology that create a digital facsimile of an actual object.

As you mentioned, you have mixed digital processes with analog means of silkscreen printing, creating frottage with oil paint, and hand-cutting stencils. At the same time, your paintings incorporate dismembered bodies, appropriated legal texts, computer screens, patents, and architectural diagrams. Could you speak about how, through these various techniques and this imagery, your paintings present a space that mixes together the three modes of place distinguished by Henri Lefebvre, that is, the mentally conceived, the subjectively perceived, and the socially lived?

I was introduced to Lefebvre in a graduate school. Lefebvre’s book The Production of Space15 was hugely revelatory to me at the time, especially as I was considering pursuing more of an urbanist line of artistic practice. After graduate school, I took a hiatus from the studio and engaged in a couple of collaborative film projects with a very close friend, Daniel Schmidt. My excitement for critical geography ended up influencing the film projects I coauthored with Daniel in their embrace of disorientating narratives about globalism and transculturation. I am attracted to filmmaking for many of the same reasons I am to painting. Both mediums have an immense, though different, capacity of compressing space, that is, all three modes of place differentiated by Lefebvre. In part, I invoke these different spatial-conceptual frameworks to challenge the medium of painting itself, to ask what is possible materially and conceptually from this primitive cultural technology. In framing painting as a cultural technology, I like to think of it as an interface that mediates between different spatial realities, between certain civilizations, bodies, or information and their representation. Painting has a membrane quality; it is a kind of skin or immunological organ that regulates what is rejected and absorbed by the body, what things are captured and what things are repelled. Moreover, the multiple layers of my compositions evoke surgical grafting. For me, there is something stupid, or wrong-headed, about eroticizing legal text or architectural diagrams, especially through painting. I attempt to integrate material processes (frottage, stenciling) and content (legal text, architectural diagrams, medieval woodcuts) that are not particularly well suited to the medium of painting, at least by conventional standards. In this way, I hope to find novel forms.

One image, in particular, stood out to me years ago; it was one of the main reasons I returned to painting after making films. The image is an unattributed woodblock from the fifteenth century, likely Germanic in origin. It depicts a brutal execution by saw, whereby a person is cut in two while suspended from a wooden frame. This scene appealed to my fascination with bodies as raw material for the state as well as for art. I imagined this split body, both alive and dead, contained within a discrete frame as an icon to exploit via the medium of painting. For me, the split body suggested the slippery relationship between the virtual and the actual as well as the mental and social spaces through which we conceive our bodies. After all, bodies are entirely material and entirely conceptual and, in both cases, wholly pluralistic in their culturally subjective terms. When it comes to spatiality and the body, I tend towards a constructivist viewpoint largely influenced by Lefebvre. Thus, it makes sense for me to invoke artifacts and abstractions such as legal texts, which are tied to a particular civilization. For me, there exists an imaginary viewer who stands on the other side of my paintings at some unknowable future moment, and the presence of these artifacts and abstractions becomes a banal marker of time, not time in the sense of physics but time in the sense of culturally subjective spatiality.

In the exhibits Call Out Tools and Bubble Revision, along with Pieter Schoolwerth and Avery Singer you presented a series of works that picture a futuristic park that the press release describes as “a radically new kind of public space that reimagines the demands of heterogeneous use.”16 Could you explain how your paintings counter the digital aspects of the bureaucratic planning and architecture and the extensive surveillance that sustain our contemporary “society of control”?17

Pieter Schoolwerth had the idea that we should all work from the same digital model for our group exhibition as a way to disrupt the banality of simply exhibiting our works alongside one another. As the three of us had all used digital tools in different capacities before in our work, it made sense to pursue a common digital space from which we could each generate paintings.

I had just finished my first solo gallery exhibition, which I designed around a satirical diagram of a hypothetical prison complex powered passively by green energy.18 For these paintings, I grafted different ideological systems and design patents into a single elegant material flow. The result was a modular prison powered by naturally occurring bioelectricity harnessed from a large monocultural banana plantation, which itself was entirely sustained by the water and nutrients contained within the prisoners’ sewage. In essence, the show revolved around the node of the prison toilet.

I wanted to continue this exploration by taking the public toilet as a theme for our group show. However, this turned out to be a bit limiting for both Pieter and Avery, so we evolved the virtual space into more of a public park in keeping with the kinds of overly designed large-scale developments that have already significantly reshaped the landscape of New York City, like Hudson Yards, the High Line, and Diller Park (currently under construction). I spent around a hundred hours designing a virtual development that consisted of large water-collecting cisterns, public baths, and conspicuously transparent public toilets. We were essentially celebrating the very dysfunctions we were attempting to satirize.

My paintings for this show became an extension of the design process. For me, what is interesting about the works I made for these shows is not so much how they counter the problems of bureaucratic planning or the perversity of large-scale urban development lensed through computer-aided design, but more so how they seem to embody these very problems. The works are subversive insofar as they represent the problem without presenting any kind of visible critique.

In recent years, you have depicted modern robotic techniques of surgery as an allegory of new digital means of representation. These images are interlaced with woodcuts rendered in reversed ground depicting medieval surgical procedures. How would you describe the very strange spatial effects that result from this strategy?

For my first solo exhibition in New York, I made a series of paintings that were inspired by biomedical technology and imaging.19 This pivot from earlier subject matter was a way for me to refocus on the body and narrow the architectural frame surrounding it from something quite sprawling like a prison complex or urban development to the more intimate and tightly controlled space of the surgical theatre. During this time, I began thinking about surgery, particularly modern surgical techniques and how I found them somewhat analogous to my idiosyncratic painting processes. While many artists now build their practices directly around the epistemological and perhaps ontological shift caused by the internet and the proliferation of virtual space, I would like to explore a more ambiguous zone where the material body is still very much the center of my work. While I do consider myself a figurative painter, I would like to believe that I am pursuing a painting that is less dependent on previous historically known styles of representation.

Perversely, I have been referencing medieval woodblocks as an extension of or amendment to the sawed figure that I discussed above. While, at first, I wanted to cut the body apart, I am now exploring some of the contradictions of that act through the analogy of surgery. In the works you are referring to, I pursued a found-image painting, whereby I superimposed and interweaved two readymade images to produce a third, destabilized space. I achieved this through a procedure of painting in layers by which a complex photographic space is rendered down into thick black lines of oil paint laid over a reverse ground medieval woodblock. In effect, this process is a graft of two readymade images in a wholly unoriginal mode of postmodern stylistic juxtaposition. Bizarrely, the resulting image completely transcends this part/whole problem and produces a genuinely novel spatial condition. They are at once textile-like tapestries in their proto-painting, proto-digital effect as much as they are entirely emblematic of a new kind of screen space or holography that we associate with advanced biomedical scans.

JOHN HOUCK

John Houck (b. 1977) has had recent solo exhibitions at Dallas Contemporary; Boesky West, Aspen; On Stellar Rays, New York; and Johan Berggren Gallery, Malmö, Sweden. He has also participated in group shows at the International Center of Photography, New York; MoMA, New York; and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). His works are held in the collections of LACMA and of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. He has an MFA from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and a BA from the University of Colorado, Boulder. He also completed the Whitney Independent Study Program and the program of the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. He lives and works in Los Angeles.

In your Aggregate series, you write a software program that you then print out and fold, and repeatedly rephotograph a number of times. Through this procedure, you push the original digital image beyond its limitations. A moiré pattern, a fringing of colors, and ghosting occur. The image oscillates. Would you say that the resulting release of energy brings into view the idea that the image has an inside, a subjectivity?

I hadn't thought about it in those terms, but I like them. For me, the “release of energy” is the fold, and maybe this interrupts the “subjectivity” of the image. The subjectivity of the image is so repetitive and overwhelming now that images are made and distributed digitally. I wanted to find some way to work through that repetition and also to interrupt it with something more human, like desire. When I first started making the Aggregates, I think the iterative loop of rephotographing them emerged out of my years of software engineering. Programming creates a very tight feedback loop of writing lines of code, compiling, and executing. When I started to make my photographs by rephotographing them, I felt a real comfort, not unlike the feeling of writing code. However, that kind of repetition also feels a bit too systematic and repetitive, which is why I quit programming and why the fold became an important element. Disrupting the flatness of the photograph and asserting some subjectivity through folding and color arrangements allowed me to interrupt photography. Additionally, like you point out, as the process accumulates errors and resolution gets lost with each step, the picture starts to oscillate.

The Aggregates expose the incompleteness lying at the heart of all algorithms. As they encounter incomputable data lying outside the limits of their logic, they produce results that appear increasingly random. Do you consider this randomness as simply incidental noise? Or do you think that these nonphysical digital images actualize new spatial forms self-organized by a nonhuman intelligence?

In computer science, completeness means that an algorithm can address all possible inputs. My algorithm largely consists of a physical and analog process, so there are a lot more variables than, say, a set of whole numbers. Like digital algorithms, though, my system can be brittle, and I have found many edges in making the Aggregates. In one instance, I rephotographed and printed out the same Aggregate pattern over twenty times. I have found that when the system goes beyond three or four iterations, it starts to become formally too wavy; it looks psychedelic. In all of my work, I have this balancing act between making a picture that looks familiar at first glance but hopefully draws you into a deeper kind of attention once you recognize its uncanny quality. I don’t think they have any kind of intelligence on their own. In graduate school, I had a real interest in emergence and chaos theory but, so often, formally all of that stuff looks very similar. It’s the collaboration between the system and me, the making physical, that creates any sort of intelligence.

In recent years, your images can be viewed simultaneously as computer-generated, photographic, and painted space. What do you accomplish through this departure from the self-critical tendency and the medium specificity of modernism?

I find the space between media more interesting. Museum curators never know which department to show the Aggregates in. They are not exactly photographs. In my work, I have moved from that initial fold to more and more gestural elements (fig. 4). The fold turned into painted marks across the surface of photos, and now into fully painted surfaces. I am continually drawn to painting because it is messier and more embodied than photography. My interest in painting also parallels my experience of undergoing psychoanalysis. Through free association, I learned to let go of my overly determined thoughts, which became really cemented through all those years of programming. I learned to be okay with the nonsense and sometimes incredible things that emerge from just saying whatever comes to mind. That process has shifted my work in the studio. Also, having trained as an architect, I put less pressure on medium specificity. In architecture, you often use a disparate set of media, and unlike the art world, you aren’t required as much to work with a specific medium.

From the beginning of your career, grids, in the form of index sheets, bit maps, and graph paper, have persisted in your works. Rosalind Krauss has written that the grid is the preeminent modernist structure. She argues that grids precede objects and their claims to have “an order particular to themselves.”20 It seems to me that in your works, the appearance of objects, such as those from your childhood sent by your parents, set in motions feelings that engender the spatial relationships of your images. As such, they contravene the notion of universal space with that of relational space. But your works do not seem to be a postmodernist attempt to deconstruct the cultural power structure. Nor do they seem to be a simple romantic affirmation of feeling over intellect. Am I right to see them as an exacting endeavor to construct space?

I do often bring forward the spatial construction of the picture. The entire History of Graph Paper series is photographs of sculptures or models. Before I touch the camera, I work spatially by arranging objects. My undergraduate training in architecture was quite modernist, but then I worked for Thom Mayne and taught at UCLA, where we thought largely in terms of Gilles Deleuze and emergence. The tension between the Cartesian grid and nonlinear space is part of that construction of space in the picture, as is the tension between formal software languages and free association. I don’t see them as a direct attempt at postmodern deconstruction, but I always reveal some of the constructedness of each work. Breaking the illusion of the picture nods to Brecht and hopefully fosters a deeper attention and observance that is increasingly rare in the way we look at pictures these days. In most of my work, I start with the notion of technical repetition and then attempt to unsettle it. Konrad Zuse, the inventor of the first programmable computer, gave this great quote: “The danger of computers becoming like humans is not as great as the danger of humans becoming like computers.” I think we need to find some way of getting outside the echo chambers and feedback loops that increasingly dictate our attention and distract us from our inner lives and relationships. I never thought the world would get to the point it is at now, and I imagine unsettling the system now will require much more than folding and painting.

ROB PRUITT

Rob Pruitt (b. 1964) lives and works in New York City. He has presented exhibitions at Air de Paris, Paris; Massimo de Carlo, Milan, London, and Hong Kong; and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York. His work has been featured in numerous museum shows, including solo exhibitions and retrospectives at the Kunsthalle Zurich, the Brant Foundation, Greenwich, CT, the Aspen Art Museum, Dallas Contemporary, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Detroit, the Freiburg Kunstverein, and Le Consortium, Dijon; and group shows at such institutions as the Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome, Tate Modern, London, the Palais de Tokyo, Paris, and Punta Della Dogana/Palazzo Grassi, Venice. In 2009, he debuted Rob Pruitt’s Art Awards, an award show for the art world at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, fashioned after the Oscars. In 2011, he was commissioned by the Public Art Fund to install The Andy Monument, a ten-foot-tall sculpture of Andy Warhol in New York’s Union Square near the site of Warhol’s Factory. Pruitt studied at the Corcoran College of Art and Design, Washington, DC, and Parsons School of Design, New York.

In 2008, you exhibited thousands of snapshots that you took with your iPhone at the gallery Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York.21 This was one of the first times, perhaps even the first time, that an artist showed photographs done with a mobile phone. You plastered the inside and even the outside walls of the gallery with them in a grid-like pattern (fig. 5). In your 2010 show at the same gallery, you covered a gigantic wall with inkjet-printed adhesive vinyl wallpaper showing thousands of emails in your Gmail inbox.22 You also wallpapered another part of the space with profile pictures of your Facebook friends. In all of these works, you seem to reflect on the blending of public and private space in the digital age. Could you tell me your thoughts on this spatial collapse?

I hadn't thought about it at the time, but these three artworks do appear stunningly similar. The iPhone photography show came out of an observational joke that the comedian Ellen DeGeneres made at the time about the ridiculousness of this new product that would function as both a phone and a camera. She mused, “what will come out next? A phone that doubles as a vacuum cleaner? A toaster phone?” I, however, loved this premise; the iPhone seemed tailor-made for my practice. I've always had a chronic desire to document my life, and since I grew up with dyslexia, I prefer visual means of documentation. Having this phone with a camera in my pocket allowed me to use my camera roll as a notebook. I never thought of my camera phone in terms of traditional photography or taking beautiful pictures; I considered it more as a way of taking notes. And, from day one, I got pretty compulsive about it. I took it out of my pocket whenever I came across a notable thing or moment that I could refer to later in my studio. As the pictures accumulated, I started to analyze my visual tendencies and patterns. There was something lyrical about this ‘stream of photography,’ so I decided to show it to an audience. I didn't consider these images as finished works but rather as all the visual ‘food’ an artist consumes to make art. They pictured what the world looked like from the inside-out. I also wanted to address the genre of self-portraiture by presenting the occasional ‘selfie.’

I've always taken an interest in the sense of community in the art world. For many artists like me, professional space and personal space tend to overlap. We develop dialogues and tight-knit friendships with fellow artists, curators, gallerists, and collectors. Oftentimes, movements and schools of thought come out of these relations. Take, for example, the close relationships in the Bloomsbury Group or how the Abstract Expressionists would all hang out together at the Cedar Tavern, forming a group. Facebook made it possible to map and track these social groups. So, for the Facebook friends work, I had the irresistible impulse to press the print button and reveal to an audience my own social group.

For the Gmail inbox wallpaper, I also disclosed details of my private life. Of course, one’s email account contains intimate personal exchanges, confidential professional correspondences, financial dealings, and health-related information. The Gmail interface always shows the beginning of each message, so by presenting these to the public, I provided a glimpse of my personal affairs. They became like teasers for an audience of people that became voyeurs. I really exposed myself in this piece; I think of it as a form of self-portraiture in the nude, perhaps my most revealing self-portrait to date.

In your well-known work Cocaine Buffet (1998), you presented a mirror with a line of real cocaine that stretched sixteen feet through the center of the space, and you invited the visitors to partake.23 You've also said that you are often interested in making art that causes a physiological change in the viewer, like ingesting cocaine. More recently, you have used the digital realm as a social space. You post regularly on Instagram, and you opened an eBay flea market – an online version of the many real-life flea markets you have organized.24 In the digital age, and especially in this COVID era of social distancing, do you think it is possible to set up an interactive shared experience as affective as your physical works?

I think that by presenting art digitally and particularly on social media, an artist can create a dialogue and cultivate intimacy with a community of people. I am less interested in the content of an individual post than in the relationships that form over time as the posts accumulate. If I have, let’s say, twenty-five thousand Instagram followers who regularly check my daily posts, a familiarity develops as the days progress. This might sound a little cynical, but in the gallery, I only really know if someone likes a work if they buy it or write a favorable review. Gauging a response from social media seems more egalitarian to me because everybody can like it, not like it, or leave a comment. In the same vein, I do believe that these social exchanges in the digital realm can produce a shared experience just as affective, if not more affective than in physical space. I often return to an idea I had for my iPhone photography exhibition. To advertise the show, we published in Artforum a picture of my hand holding an iPhone, which connected the image on-screen to the body. When people view something you've made on their phone, it creates an intimate relationship more likely to trigger a physiological change than looking at an artwork in a physical exhibition space. For example, I can look at a friend’s work on my phone while lying in bed, and that, for me, sets up an inevitably more connected response.

In addition to this dissolution of the boundaries between public and private and work and play instituted by international corporations, our cultural identity is no longer grounded in a sense of place but rather organized in a “code space”25 where the preeminent institutions – Amazon, Facebook, Instagram, Google, eBay, etc. – determine value through a machine order incomprehensible to humans. I don’t see your complicity with these platforms, with consumerism, celebrity, marketing, and popular entertainment as an ironic critique or an attempt at accelerationism. In your work, how do you retain the enjoyment of these things, the enchantment of digital technologies, while still escaping their control?

I do not attempt to dismiss these platforms or promote them. I want to figure them out from the inside while they are still new and relevant. Sometimes I do include an ironic twist. For example, with my eBay store, I donate the profits to charity, thereby opposing the pure capitalism of eBay with philanthropism. At the same time, I actively try to let these institutions control me, like when you go to a party and let yourself get as drunk as you can or when you dive into the pool to see how deep it can take you. By being a willing participant, I can document the experience as it happens. That said, I've always had a talent in my life for maintaining self-control, the ability to walk away from things before they become a serious problem. Having attention deficit disorder might contribute to this. I start to get bored with things and move on to something else. Also, too much stuff still occurs in the space of real life to get completely sucked in by these virtual platforms. For instance, I set up an Instagram page for my puppy, Gilda, to post all the cute things she does, like playing fetch and getting belly rubs. But I like to explore the juxtaposition of this virtual space and the things that occur entirely off-screen.

In your exhibition Pattern and Degradation you were inspired by “Rumspringa”, the Amish rite of passage that allows a teenager to leave the community temporarily to play in the outside world and indulge in rebellious, prohibited activities. You have said that the role of the artist is to live in a “permanent Rumspringa.” Today, power is no longer exercised in the enclosed spaces of the school, the hospital, the factory, etc. The space of work and play all take place on the same computer or phone. Moreover, with “playbor,” when we surf the net, go on Facebook and Instagram, etc. our play becomes productive for corporate profit.26 There is no inside or outside. Is it possible today to find a free place of play comparable to the Rumspringa?

For sure, I agree that corporations profit from our internet activity to mine our data and monetize our information. But I believe we can get beyond this by participating in social media and the internet as voyeurs and exhibitionists. Digital platforms allow us to operate in the shadows of real life. They give the voyeurs the option to play the exhibitionist and the exhibitionists the opportunity to play the voyeur. In this way, we can all play freely and anonymously. And, after exploring these roles, we can return to real life with a better understanding of who we are and who we want to become.